Scotland's public health time bomb is ticking

16 July 2020

Guest comment: We face a welfare crisis unless parents receive more support before conception and over a child’s first 1000 days, argues Alan Sinclair

There’s a time bomb tucked away in an obscure report published by the Scottish Government in August 2019.

It reveals the alarming discovery that a majority of two-year-old children eligible and attending day-care lacked crucial life skills; attributes they need if they are to be healthy and valued members of society. Without these skills they will be doomed to lesser lives with higher risk of ending up in jail, unemployment, hospital or care.

Sad to say the bomb is going off in a spot where public policy has failed to respond to a scientific fact. In the 1,000 days between conception and two years of age, children undergo the most vital stage of their whole developmental journey.

That said, we must acknowledge the good intent of the Scottish Government to improve the lives of young children. Evidence: the rediscovery of the Health Visitor service, expansion of early learning and childcare and the Care Review. But we need to build on this by giving more support to parents from before conception till the child is at least two years of age.

The bomb

The Scottish Government hired the Scottish Centre for Social Research to gather a baseline of data on two-year-old children eligible and receiving 600 hours of funded childcare. ScotCen collected data from parents and key workers on 574 two-year-olds.

All of the children lived in households receiving certain state benefits, were looked after or in care. They were drawn from 17 local authority areas and 151 day-care settings. Close to 50% of the households were led by a single parent and 50% of the households had an annual income of less than £9,701.

The good news is that, two out of three parents reported that early learning and care enabled them to think more about the future, a slightly smaller number felt less stressed and just over half felt happier.

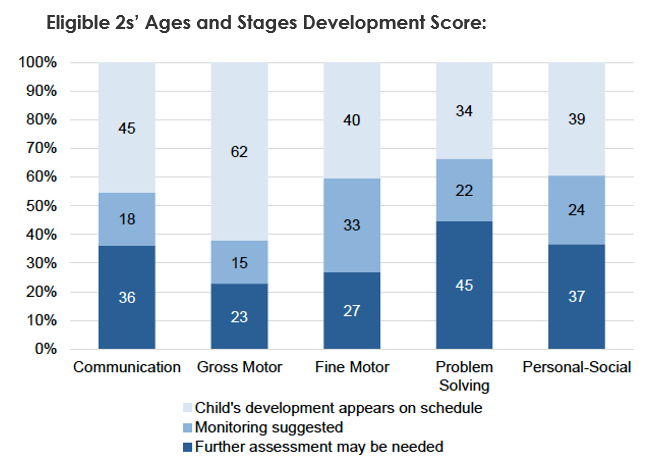

Children’s key workers were asked to make observations of the child’s development using the internationally recognised Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ). In this process the child’s development is assessed across five life skill categories: communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem solving and personal-social. Scottish health visitors use the same questionnaire.

The results are set out below:

The proportion of children not meeting their development goals is captured in the dark blue part of the diagram. In fine motor skills, problem-solving and personal-social, six out of 10 of the children are not meeting the expected child development standard. More than one out of two are behind in communication.

At this point you need to stop and pause and let the bomb go off.

It is tempting to think that the best will happen; children will grow out of it. Perhaps a few children will catch up. But for the majority that thinking is delusional.

If you do not have these life skills at two years of age, the foundation is missing and all of subsequent life is more likely to be impaired. I repeat: the majority of children do not catch up.

Mother nature sets the rules

Mother nature and science give us three clear messages about child development:

- Child development is sequential. Like house building, the site, drainage, and foundation need to be right before the walls go up. Babies need a healthy pregnancy and good early attachment to thrive.

- Child development is cumulative. It builds, good upon good, bad upon bad. Good attachment and healthy stimulation make it easier for a child to have relationships and prosper at school. Neglect or a series of adverse childhood experiences make it harder for a child to learn and cope with life.

- Child development starts before conception and peaks from womb through to two years of age. On the downside, folic acid deficiencies, alcohol and drugs and toxic stress all kick in from before and during the first days in the womb.

We can see from the ScotCen report that more than one out of two children studied are behind their developmental milestones. If this were the equivalent of a life course presented in a nursery school sports day, you would see a group of children sprinting ahead. Way behind with tethered legs come the fallers and stragglers. Is this over-dramatic?

Closely watch life unfold

What if we monitored a group of 1,000 children between the ages of two and three? Recorded their key characteristics as small children and then faithfully followed up as adults to see what happened to them at, say 38 years of age?

We do not need to wait. In 1972 in New Zealand, the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Programme followed the entire group of children born that year in the city, just over 1,000. This group with few dropouts are contenders for being the most intensively studied group of people in the world.

What the researchers found was that 22% of the children when they became 38-year-old adults were responsible for: 81% of criminal convictions; 78% of prescriptions; 77% of fatherless child rearing; 66% of welfare benefits and 57% of hospital nights.

In examining the data of the 22% of the children/adults that carried the greatest burden, one predictor stood out: “brain health” at age three. It involved a neurological examination and assessments of verbal comprehension, language development, motor skills and social behaviour. Not exactly the same assessments as the ASQ, but close enough.

The research team behind the study agree on their most significant finding: “Self-control in childhood is more important than socio-economic status or IQ in predicting adults’ physical health, wealth, life satisfaction, addiction, crime and parenting of the next generation.”

Lessons to be learned

Dunedin helps to show that poor mental and physical health, inadequate attainment at school, criminal behaviour and substance abuse are not different problems; the root is the same and lies in the first 1000 days.

A group of 574 children might be too small a sample to make a big bomb. The children in the Scottish sample attend day-care. We do not know if the parents of eligible two-year-olds who do not attend day-care are doing better or worse in meeting development milestones.

From other government sources we know a big number of very young children are not getting a proper start. In 2017-18, one out of four children taken into care is under 20 days old. They are being protected from “significant harm or likelihood of significant harm”. Children under the age of one are the fastest expanding group going into care. Under-ones are the most murdered age group in Scotland according to homicide figures (click to read).

Covid-19 has paused the expansion of day-care. When the virus allows, it makes sense to move on. The current no-man’s land from preconception to two years of age is in need of being reclaimed. Vulnerable babies have vulnerable parents. Many day-care workers and health visitors are frustrated but what can an individual do when day care starts at two years of age or they have 749 other parents and children to see.

Parenting is joyous and frustrating. But like Covid-19 it is a public health issue. We should know by now that prevention and early intervention work best and that blind spots (think care homes) are best avoided.

The sense of direction is clear: children benefit throughout life if they have good self-control and life skills by three years of age. This is about having the will to do it.

Alan Sinclair started Heatwise Glasgow and the Wise Group, where he was Chief Executive for 17 years. He was the Senior Director for Skills and Learning at Scottish Enterprise and was given a CBE for training unemployed people in 2000. He has been studying Scotland’s poor child wellbeing performance for more than a decade. His findings and conclusions were published in 2018 in Right From the Start, part of the Postcards from Scotland series of books.

We expect and encourage responses to this guest opinion piece, published as part of our contribution to dialogue in the sector across the full breadth of policy issues relating to children, young people and families.

About the author

Alan Sinclair was CEO of the Wise Group for 17 years and is author of Right from the Start

Click to find out more

Study of early learning and childcare

Find out more about the Phase One Scottish study of early learning and childcare

Click to visit the websiteScottish Centre for Social Research

ScotCen, based in Edinburgh, is part of NatCen Social Research, Britain’s leading centre for independent social research

Click to find out moreAges and Stages Questionnaire

More about the internationally recognised developmental assessment

Click to visit the website

The Dunedin Study

A detailed study of human health, development and behaviour, based in Dunedin, New Zealand

Click to find out more

Independent Care Review

The review's final report was published in February 2020

Click to read our response

"Inequality challenge is still top priority"

In April we responded to news that the childcare expansion was being put on hold

Click to read our press release

"Childcare expansion delay must not risk losing focus"

Future expansion as an opportunity to secure positive outcomes for children, writes Gemma Paterson

Click to read her guest comment

CHANGE

An innovative project supporting childcare development in East Glasgow

Click to find out more